Many of you, our classmates, served in the military after graduation. This web page has been created for you to share personal stories related to your service. If you have a story you wish to share with the rest of our class, please send it to me, Earl Buckingham, via e-mail at earlbuck@twcny.rr.com.

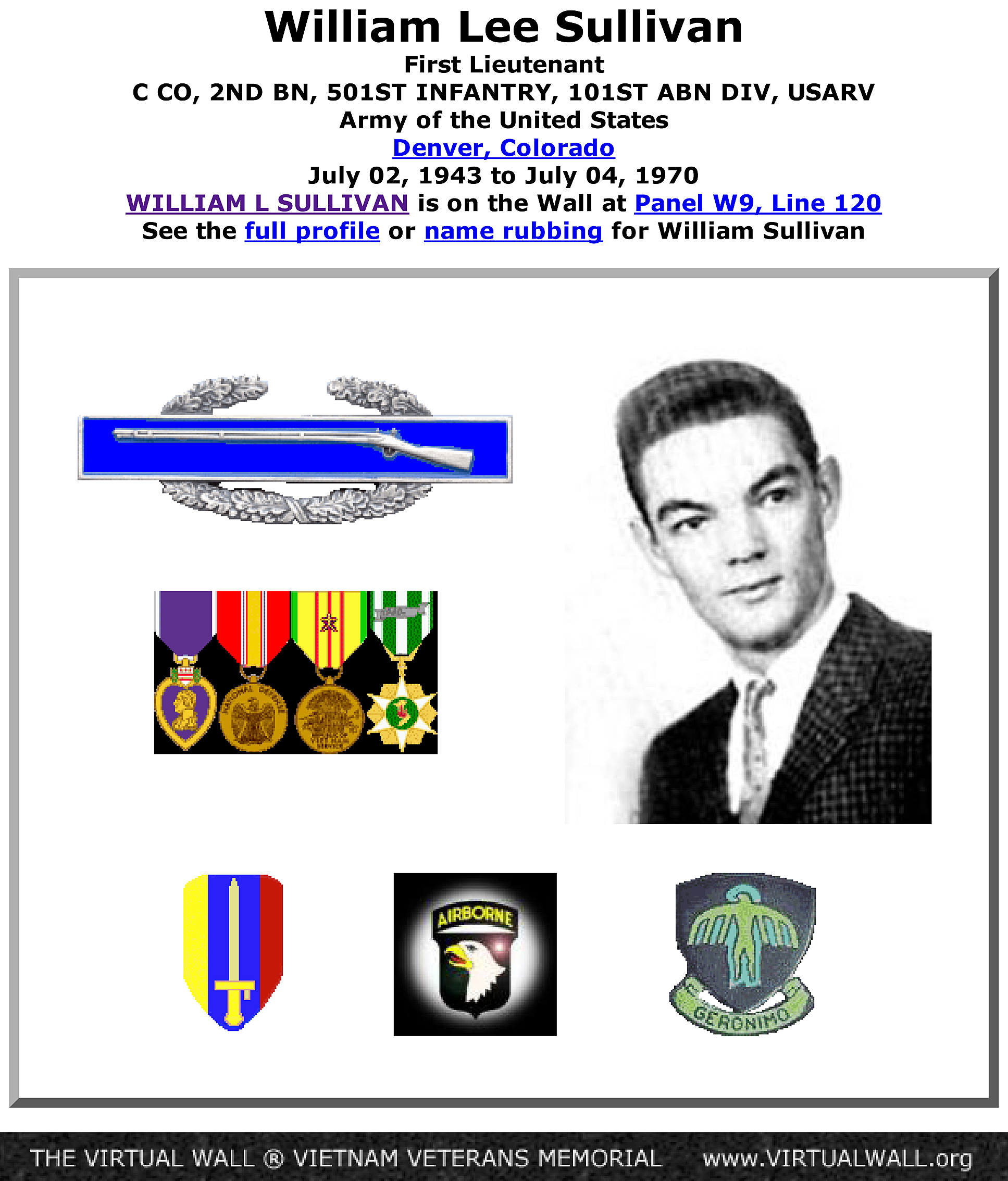

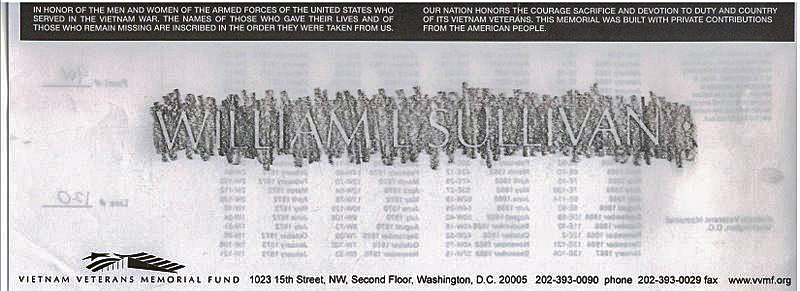

Our classmate, Bill (L) Sullivan was killed in action in Vietnam. Bill was the only one of our classmates to die in that war. He served as a 1st Lieutenant of Infantry. He was a Unit Commander in C Company, 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division, US Army-Republic of Vietnam. He was killed on July 4, 1970. He was 27 years old. On that day, Bill volunteered to go on patrol, substituting for a comrade, who had just completed a patrol. Bill went in his place so his friend could rest and recover. This incident is discussed by Nancy Nersessian, the sister of David Nersessian, in an interview documented in the Favorite Poem Project. To see and hear the interview just click here. Below is a rubbing of Bill's name engraved on Panel #9W, Line #120 of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C. To see the Vietnam Memorial Virtual Wall, Click here.

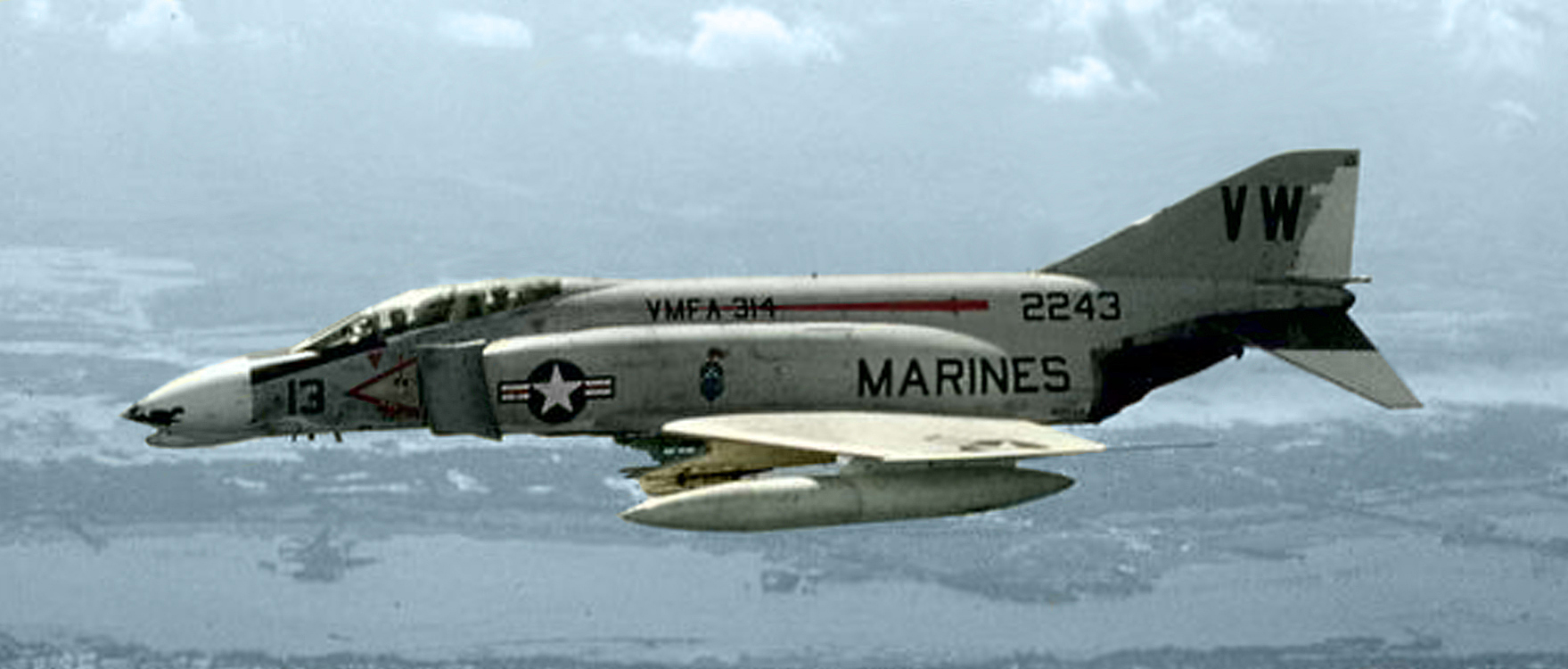

John Tuthill served as a U.S. Marine Corps fighter pilot and flew in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. He wrote the following about a signature moment he experienced in August 1981. John's call sign as an F-4 Phantom II pilot was "Ironside." The article was published in the April 1986 issue of the Marine Gazette. John graciously gave permission for the posting of this article on our website.

I spent a year and a half in Vietnam as an artillery officer. My battalion (175mm guns) was embedded in the Marines at Camp Carroll, up near the DMZ -- the only Army unit anywhere near there, so I got to know the Marines. Interesting bunch of folks :)

I enjoyed John Tuthill's story. Certain parts of it resonate and bring back memories. Partly the attitude that comes through. Partly that many of the place names in his story are sure familiar -- my battalion shot in support of the men in many of those same places, although a couple of years earlier than John's experience.

His story reminds me of talking with the Marines about close air support. There was no doubt that the Marines on the ground very strongly preferred close air support to be done by Marine pilots. It was not just Semper Fi, pride in the Corps -- they felt that the Marine pilots understood those on the ground better and were therefore safer to be around. They gave me a couple of good examples to illustrate their point.

I think I can somewhat understand John's feelings about those eight Marines. I was the night shift battalion fire direction officer and I remember how good it felt to get those thank-you notes saying something along the lines of "Hill XXX could not have held out last night without your guns."

One effect of those times which I notice these days is that whenever I look at someone doing an important task and they look young to me, I think of what age we were and the responsibilities we had in Vietnam.

John David served in the U.S. Navy after High School. He was trained as a Fire Control Technician on the very new Terrier surface to air missile system. After he completed technical school, he served over two years on the USS Dahlgren, DLG-12, a new (at the time) guided missile destroyer. He wrote the following about experiencing rough weather at sea.

I went aboard my ship, USS Dahlgren, in November 1962, just after she returned from blockade duty during the Cuban crisis. I had spent a year in technical school studying to be a Fire Control Technician or, as we called them, an “FT.” I had been trained to maintain and operate a brand new analog computer that was the brains of the fire control system that targeted, launched, and controlled one of the first surface-to-air missiles deployed in the U.S. Navy, the Terrier Missile. The USS Dahlgren was state of the art at the time and had only been in commission for just over a year when I went aboard. She was about 500 feet long with a beam of 52 feet. Her displacement (the weight of water she displaced while floating) was 5,900 tons. She had a crew of 370 men and officers.

When I reported aboard, I found out that, in addition to working on the computers on which I had been trained, I had other duties assigned to me on the “Watch, Quarter, and Station Bill.” Among the additional duties I had was an underway watch as helmsman, steering the ship for four hours twice a day when we were at sea. This turned out to be both one of the most boring duties and one of the most exciting duties I had while in the Navy. It was boring while on watch from midnight until four in the morning in calm seas with no course changes. Ho Hum! But, when we were involved in antisubmarine exercises, chasing a submarine at high speed and making drastic course changes, the four-hour watch went really quick.

I never saw combat in my Navy career so I have no personal experiences such as those told by our classmates John Tuthill and Bob Blean. I did, however, experience some terrifying times (to me, at least) while at sea. My ship was home ported at the Naval Operating Base, Norfolk, Virginia, so we spent most of our time at sea in the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. As you know, hurricane season in those bodies of water runs for six months, from June through November. In the latter part of September, 1963, we were operating in the Caribbean when Hurricane Flora came through. We, at the time were in harbor at San Juan, Puerto Rico having just completed a missile firing exercise on a range at sea near Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico. The path of Flora was projected to pass right through Puerto Rico so we left harbor to ride out the hurricane at sea where we could maneuver. To prepare for the storm, anything that was not permanently attached to the ship was tied down and lines were rigged in all passageways for the crew to hold onto when having to move around the interior of the ship. We left port in the early morning and as we cleared the harbor, the sea was already up with waves about five to six feet high. Lunch that day was our last hot meal for two days. Once we had cleared land, we set the underway watch which meant I would stand helm watch eight hours a day in two watches of four hours each. The seas grew to somewhere between 15-30 feet as we tried to maintain a course to minimize damage to the ship. Being the helmsman, I just responded to the helm orders given to me by the officer of the Conn. I stood on wooden grating at a console with a gyroscopic main compass, a magnetic backup compass, and a helm/rudder indicator on it. I held onto a large brass wheel that was the actual helm, controlling the position of the ship’s rudder. We were receiving green water over the pilothouse and bridge while I was on watch between 12:00 PM and 4:00 PM. Our bow was submerging into the waves and rearing up like a horse only to sink back and start all over again. The crew not on watch was ordered to stay strapped in their bunks to avoid injury. There was no food being prepared and the only food available (if you could get to it) was sandwiches stacked in containers on the mess deck. As we maneuvered to keep our bow into the wind, the ship would roll 15 to 30 degrees from vertical and, from my position, hanging onto the helm; I could look “down” and see the water out the bridge wing door porthole. I had to hang on to keep from sliding down the pilothouse deck towards the bridge wing. At one time, the inclinometer on the bulkhead indicated a roll to starboard of almost 40 degrees. I didn’t think we would recover from that one. Several members of the watch slid down the deck and would have fallen into the sea if the bridge wing door had been open. The wooden grating I was standing on slid out from under me and went crashing into the bulkhead. I was hanging on to anything I could grab on the consol just trying to keep control of the rudder. The ship slowly rolled back to port and, as we passed through vertical, the speed of the roll increased significantly, tossing everyone towards the port bridge wing. The ship finally recovered when we settled on the new course. I later learned that the ship lost all of the lifelines on the starboard side and the 26 foot motor whale boat was washed away. After being relieved from my watch, I carefully made my way back to my berthing compartment, grabbing a couple of sandwiches on the way. I strapped myself into my bunk and waited the eight hours before my next watch at midnight.

Dave Franklin joined the Army after he graduated from Cornell. He tells the following tale of his experiences during a tour of duty as an Armor Officer.

My wife of 47 years and I were married 2 days before I graduated from Cornell in'65. She was a junior and wanted to graduate from Cornell, so we stayed in Ithaca and I took a job as credit manager of the local Goodyear tire store. The number ten is indelibly ingrained in my mind since the 10th of December 1965 I received my draft notice to report to the Syracuse induction center for a physical as my "friends and neighbors" at the local draft board saw a different use of my time and talents. Ten days later I received another letter informing me that I had passed and that I should again report to the Syracuse induction center on February 15, 1966 for induction into the US Army. I immediately went to the local Army recruitment center (since I had been asked to leave the Cornell Naval ROTC program after a sorority panty raid caper, and had later quit the Cornell Air Force ROTC program) as they seemed like the only option where I might have any leverage at all. They agreed that if I enlisted and passed another battery of tests that I would be guaranteed officer candidate school in the branch of my choice. I signed on the dotted line and chose Armor as that seemed to be a lot thicker than a fatigue jacket if I was going to draw any serious fire. We have called Valentine's Day, the Last Supper in the Franklin family since as I took my wife to dinner on Valentines Day and the next morning she drove to to Syracuse where I was placed on a train to Fort Knox, Kentucky after being sworn into the service of my country.

My first 9 days in the service were dedicated to head shaving, shots and more shots, uniform issues, and KP every day peeling potatos. I still hate to peel potatos. Then after 8 weeks of basic training, followed by 9 weeks of advanced individual training (during which I found out that we were pregnant with our first child, Heather Anne) my OCS class started July 5th. I was commissioned after 23 weeks of abuse as a Second Lieutenant Armor, and sent to another 15 weeks of motor officer school at Fort Knox. I was told I could make two selections for duty stations. I picked Hawaii and Alaska, and was assigned to Germany, on an unaccompanied (no wife or child paid for by the US Army) tour. I chose to pay my wife and daughters way to Germany and was told we had to live in Government quarters even though the Army had not paid the family's passage or I would forfeit my housing allowance. Welcome to Baumholder Officer's quarters Sharon and Heather. I was assigned to Regimental Headquarters as a training officer and spent about 60-70 percent of the next two years in the field.

Between marriage and the responsibilities of a child the service was, in retrospect, the BEST THING that could have happened to us. It forced me to grow up in a hurry, and become responsible, not the tack that I had followed during my four college years at Cornell. We got to see most of Western and central Europe, met some life long friends, and had some of the best role models as leaders that I ever had, including my 40 subsequent years in corporate America. My unit was transferred enmass from Germany to Fort Lewis, Washington when I had less than six months to fulfill my commitment and we were introduced to God's Country where we have since retired. I look back fondly on those years and feel strongly that every American should have to devote at least two years to the country in some capacity other than elected office or civil servant.